List of medieval Mongol tribes and clans

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

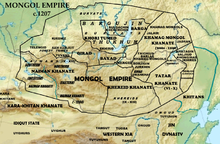

The qualifier Mongol tribes was established as an umbrella term in the early 13th century, when Temüjin (later Genghis Khan) united the different tribes under his control and established the Mongol Empire. There were 19 Nirun tribes (marked (N) in the list) that descended from Bodonchar and 18 Darligin tribes (marked (D) in the list),[1] which were also core Mongolic tribes but not descending from Bodonchar. The unification created a new common ethnic identity as Mongols. Descendants of those clans form the Mongolian nation and other Inner Asian people.[citation needed]

Almost all of tribes and clans mentioned in the Secret History of the Mongols [2] and some tribes mentioned in the Tarikh-i-Rashidi, there are total 33 Mongol tribes.[citation needed]

Core Mongolic tribes

[edit]- Khori-Tumed

- Khorilar

- Dorben (N)

- Uriankhat

- Ma'alikh baya'ut (D)

- Jarchi'ut Adangkhan (D)

- Belgunot

- Bugunot

- Khatagin (N)

- Eljigin

- Salji'ut

Keraites

[edit]The Keraites were a Turco-Mongol Christian (Nestorian) nation.[3][4] Prominent Christian figures were Tooril and Sorghaghtani Beki.

Tatar confederation

[edit]Tatars were a major tribal confederation in the Mongolian Plateau.

- Airi'ut, mentioned in connection with Ambakhai's death

- Buiri'ut, mentioned in connection with Ambakhai's death

- Juyin other Tatars, or maybe a military organization, mentioned in connection with Ambakhai's death

- Chakhan Tatar, mentioned in connection with the final destruction of the Tatar; Mongolian: Tsagaan Tatar

- Alchi Tatar, mentioned in connection with the final destruction of the Tatar

- Duta'ut Tatar, mentioned in connection with the final destruction of the Tatar

- Alukhai Tatar, mentioned in connection with the final destruction of the Tatar

- Tariat Tatar[5]

Merkit confederation

[edit]The Merkits was a Mongol tribe or potentially a Mongolised Turkic group[6][7] who opposed the rise of Temüjin, and kidnapped his new wife Börte. They were defeated and absorbed into the Mongol nation early in the 13th century.

- Uduyid; Mongolian: Uduid Mergid

- Uvas, Uvas Mergid

- Khaad, Khaad Mergid

Naimans

[edit]In The Secret History of the Mongols, the Naiman subtribe the "Güchügüd" are mentioned. According to Russian Turkologist Nikolai Aristov's view, the Naiman Khanate's western border reached the Irtysh River and its eastern border reached the Mongolian Tamir River. The Altai Mountains and southern Altai Republic were part of the Naiman Khanate.[8] They had diplomatic relations with the Kara-Khitans, and were subservient to them until 1175.[9] In the Russian and Soviet historiography of Central Asia they were traditionally ranked among the Mongol-speaking tribes.[10] For instance, such Russian orientalists as Vasily Bartold, Grigory Potanin, Boris Vladimirtsov, Ilya Petrushevsky, Nicholas Poppe, Lev Gumilyov, Vadim Trepavlov classified them as one of Mongol,[10] Other scholars classified them as a Turkic people from Sekiz Oghuz (means "Eight Oghuz" in Turkic).[11][12][13] However, the term "Naiman" has Mongolian origin meaning "eight", but their titles are Turkic, and they are thought by some to be possibly Mongolized Turks. They have been described as Turkic-speaking, as well as Mongolian-speaking.[13] Like the Khitans and the Uyghurs, many of them were Nestorian Christians or Buddhists.[14]

Ongud

[edit]The Ongud (also spelled Ongut or Öngüt; Mongolian: Онгуд, Онход; Chinese: 汪古, Wanggu; from Old Turkic öng "desolate, uninhabited; desert" plus güt "class marker"[15]) were a Turkic tribe that later became Mongolized active in what is now Inner Mongolia in northern China around the time of Genghis Khan (1162–1227).

Many Ongud were members of the Church of the East, They lived in an area lining the Great Wall in the northern part of the Ordos Plateau and territories to the northeast of it.[16]

Dughlat

[edit]The Dughlats are mentioned in the Jami' al-tawarikh.

Other groups mentioned in Secret History of the Mongols

[edit]Groups whose affiliation is not really made clear: these groups may or may not be related to any of the tribes and clans mentioned above:

- Olkhonud, the clan of Temüjin's mother (D); Mongolian: Olkhunuud

- Khongirad, the tribe Börte, Temüjin's first wife, descends from (D)

- some clans whose members join Temüjin after the first victory over the Merkit and the separation from Jamukha:

- some clans that take part in Sangums conspiracy:

- Khardakit

- Ebugedjin; Mongolian: Övögjin

- Kharta'at (N?)

- Khorulas, clan that joins Chinggis at the Baljun lake

- Tokhura'ut

- Negus or Chonos tribe, clan whose chief is killed together with the 70 Chinos princes

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, Jami' al-tawarikh

- ^ Erich Haenisch, Die geheime Geschichte der Mongolen, Leipzig 1948

- ^ R. Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1970, p191.

- ^ Moffett, A History of Christianity in Asia pp. 400-401.

- ^ Tarikh-i Rashidi

- ^ Soucek, Branko; Soucek, Svat (2000-02-17). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65704-4.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- ^ "Augustine", Routledge History of Philosophy Volume II, Routledge, pp. 410–454, 2003-09-02, doi:10.4324/9780203028452-21, ISBN 9780203028452, retrieved 2022-06-27

- ^ Biran, Michal (2020-06-30), "The Qara Khitai", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.59, ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7, retrieved 2022-06-27

- ^ a b Hanak, Walter K. (April 1995). "Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy.Paul Ratchnevsky, Thomas Nivison Haining". Speculum. 70 (2): 416–417. doi:10.2307/2864944. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2864944.

- ^ Czaplicka, Marie Antoinette (2001). "The Turks of Central Asia in History and at the Present Day". Oxford. JSTOR 1780419.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1987). A history of the Crusades. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34770-X. OCLC 17461930.

- ^ a b Jullien, Christelle (2021-01-18). "Li Tang, Dietmar W. Winkler (eds.). Artifact, Text, Context: Studies on Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia". Abstracta Iranica. 42. doi:10.4000/abstractairanica.54181. ISSN 0240-8910 – via OpenEdition Journals.

- ^ Verlag, Lit (2009). Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters. 2. Auflage: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643500458.

- ^ Rybatzki, Volker (2004). "Nestorian Personal Names from Central Asia". Studia Orientalia. 99: 269–291 – via journal.fi.

- ^ "元史/卷118 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org (in Chinese). Retrieved 2022-06-26.