Beggars Banquet

| Beggars Banquet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

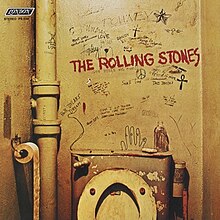

Original LP cover | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 6 December 1968 | |||

| Recorded | 17 March – 25 July 1968 | |||

| Studio | Olympic, London;[1] Sunset Sound, Los Angeles | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:44 | |||

| Label | Decca (UK) · London (US) | |||

| Producer | Jimmy Miller | |||

| The Rolling Stones chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternate cover | ||||

The "toilet" cover, rejected for the original LP, but used on subsequent reissues | ||||

| Singles from Beggars Banquet | ||||

| ||||

Beggars Banquet is the seventh U.K. and ninth U.S. studio album by the English rock band the Rolling Stones, released on 6 December 1968 by Decca Records in the United Kingdom and by London Records in the United States. It was the first Rolling Stones album produced by Jimmy Miller, whose production work formed a key aspect of the group's sound throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Brian Jones, the band's co-founder and early leader, had become increasingly unreliable in the studio due to his drug use, and it was the last Rolling Stones album to be released during his lifetime, though he also contributed to two songs on their next album Let It Bleed, which was released after his death (Jones also contributed to the group's hit song "Jumpin' Jack Flash", which was part of the same sessions, and released in May 1968). Nearly all rhythm and lead guitar parts were recorded by Keith Richards, the Rolling Stones' other guitarist and the primary songwriting partner of their lead singer Mick Jagger; together the two wrote all but one of the tracks on the album. Rounding out the instrumentation were bassist Bill Wyman and drummer Charlie Watts, though all members contributed on a variety of instruments. As with most albums of the period, frequent collaborator Nicky Hopkins played piano on many of the tracks.

Beggars Banquet marked a change in direction for the band following the psychedelic pop of their previous two albums, Between the Buttons and Their Satanic Majesties Request.[2] Styles such as roots rock and a return to the blues rock sound that had marked early Stones recordings dominate the record, and the album is among the most instrumentally experimental of the band's career, as they use Latin beats and instruments like the claves alongside South Asian sounds from the tanpura, tabla and shehnai, and African music-influenced conga rhythms.

Beggars Banquet was a top-ten album in many markets, including a number 5 position in the US—where it has been certified platinum—and a number 3 position in the band's native UK. It received a highly favourable response from music critics, who deemed it a return to form. While the album lacked a hit single at the time of its release, songs such as "Sympathy for the Devil" and "Street Fighting Man" became rock radio staples for decades to come. The album has appeared on many lists of the greatest albums of all time, including by Rolling Stone, and it was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999.

Recording and production

[edit]Glyn Johns, the album's recording engineer and a longtime collaborator of the band, said that Beggars Banquet signalled "the Rolling Stones' coming of age. ... I think that the material was far better than anything they'd ever done before. The whole mood of the record was far stronger to me musically."[6] Producer Jimmy Miller described guitarist Keith Richards as "a real workhorse" while recording the album, mostly due to the infrequent presence of Brian Jones. When he did show up at the sessions, Jones behaved erratically due to his drug use and emotional problems.[6] Miller said that Jones would "show up occasionally when he was in the mood to play, and he could never really be relied on:

When he would show up at a session—let's say he had just bought a sitar that day, he'd feel like playing it, so he'd look in his calendar to see if the Stones were in. Now he may have missed the previous four sessions. We'd be doing let's say, a blues thing. He'd walk in with a sitar, which was totally irrelevant to what we were doing, and want to play it. I used to try to accommodate him. I would isolate him, put him in a booth and not record him onto any track that we really needed. And the others, particularly Mick and Keith, would often say to me, 'Just tell him to piss off and get the hell out of here'.[6]

Jones contributed to eight tracks on the album, playing sitar[7][8] and tanpura on "Street Fighting Man",[9] slide guitar on "No Expectations", harmonica on "Parachute Woman", "Dear Doctor" and "Prodigal Son",[10] acoustic guitar and backing vocals on "Sympathy for the Devil",[11] and Mellotron on "Jigsaw Puzzle" and "Stray Cat Blues".[12] In a television interview, Mick Jagger recalled that Jones' slide guitar performance on "No Expectations" was the last time he contributed something with care. Other than Jones, the principal band members appeared extensively, with Richards providing nearly all of the lead and rhythm guitar work, as well as playing bass on two others, in the place of Bill Wyman, who appears on the rest. Drummer Charlie Watts plays the drum kit on all but two tracks, as well as other percussion on the tracks that do not feature a full drum kit. Additional parts were played by keyboardist and frequent Rolling Stones collaborator Nicky Hopkins and percussionist Rocky Dijon, among others.

The basic track of "Street Fighting Man" was recorded on an early Philips cassette deck at London's Olympic Sound Studios, where Richards played a Gibson Hummingbird acoustic guitar, and Watts played on an antique, portable practice drum kit.[13] Richards and Jagger took credit as writers on "Prodigal Son", a cover of Robert Wilkins's Biblical blues song.[6]

Celebrating the completion of the album, Jagger held a party at Vesuvio's nightclub in Central London. Paul McCartney attended with an acetate copy of "Hey Jude". The song upstaged Beggars Banquet and, in author John Winn's description, "reportedly ruin[ed]" the party.[14]

Packaging

[edit]According to Keith Richards, the album's title was thought up by British art dealer Christopher Gibbs.[15] The album's original front and back cover art, photographs by Barry Feinstein depicting a bathroom wall covered with graffiti, was rejected by the band's record company,[16][17] which delayed the album's release for months.[6] Feinstein's photographs were later featured though on most vinyl, compact disc and cassette tape reissues of the album.[6][18] On 7 June 1968, a photoshoot for the album's gatefold, with photographer Michael Joseph, was held at Sarum Chase, a mansion in Hampstead, London.[19] Previously unseen images from the shoot were exhibited at the Blink Gallery in London in November and December 2008.[20]

Release and promotion

[edit]Beggars Banquet was first released in the United Kingdom by Decca Records on 6 December 1968, and in the United States by London Records the following day.[21] Like the band's previous album, it reached number three on the UK Albums Chart, but remained on the chart for fewer weeks.[22] The album peaked at number five on the Billboard 200.[23]

On 11–12 December 1968 the band filmed a television extravaganza titled The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus featuring John Lennon, Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, The Who, Jethro Tull and Marianne Faithfull among the musical guests.[24][25] One of the original aims of the project was to promote Beggars Banquet, but the film was shelved by the Rolling Stones until 1996, when their former manager, Allen Klein, gave it an official release.[26]

Critical reception

[edit]Beggars Banquet received a highly favourable response from music critics,[27][28] who considered it a return to form for the Stones.[29][30] Author Stephen Davis writes of its impact: "[The album was] a sharp reflection of the convulsive psychic currents coursing through the Western world. Nothing else captured the youthful spirit of Europe in 1968 like Beggars Banquet."[28]

According to music journalist Anthony DeCurtis, the "political correctness" of "Street Fighting Man", particularly the lyrics "What can a poor boy do/'Cept sing in a rock and roll band", sparked intense debate in the underground media.[6] In the description of author and critic Ian MacDonald, French director Jean-Luc Godard's filming of the sessions for "Sympathy for the Devil" contributed to the band's image as "Left Bank heroes of the European Maoist underground", with the song's "Luciferian iconoclasm" interpreted as a political message.[31]

Time described the Stones as "England's most subversive roisterers since Fagin's gang in Oliver Twist" and added: "In keeping with a widespread mood in the pop world, Beggars Banquet turns back to the raw vitality of Negro R&B and the authentic simplicity of country music."[32] Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone considered that the band's regeneration marked the return of rock'n'roll, while the Chicago Sun-Times declared: "The Stones have unleashed their rawest, rudest, most arrogant, most savage record yet. And it's beautiful."[32]

Less impressed, the writer of Melody Maker's initial review dismissed Beggars Banquet as "mediocre" and said that, since "The Stones are Mick Jagger", it was only the singer's "remarkable recording presence that makes this LP".[33] Geoffrey Cannon of The Guardian found that the album "demonstrates [the group's] primal power at its greatest strength" and wrote admiringly of Jagger's ability to fully engage the listener on "Sympathy for the Devil", saying: "We feel horror because, at full volume, he makes us ride his carrier wave with him, experience his sensations, and awaken us to ours."[34] In his ballot for Jazz & Pop magazine's annual critics poll, Robert Christgau ranked it as the third-best album of the year, and "Salt of the Earth" the best pop song of the year.[35] In April 1969, for Esquire, he wrote that Beggars Banquet is "unflawed and lacking something", in contrast to the Beatles' latest, Abbey Road, which "is flawed and great anyway."[36]

Reappraisal

[edit]| Retrospective professional reviews | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 87/100 (50th anniversary)[37] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| And It Don't Stop | A[38] |

| Boston Herald | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[41] |

| The Great Rock Discography | 10/10[42] |

| MusicHound Rock | 4.5/5[43] |

| NME | 8/10[44] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

In a retrospective review for Wondering Sound, Ben Fong-Torres called Beggars Banquet "an album flush with masterful and growling instant classics", and said that it "responds more to the chaos of '68 and to themselves than to any fellow artists ... the mood is one of dissolution and resignation, in the guise of a voice of an ambivalent authority."[46] Colin Larkin, in his Encyclopedia of Popular Music (2006), viewed the album as "a return to strength" which included "the socio-political 'Street Fighting Man' and the brilliantly macabre 'Sympathy for the Devil', in which Jagger's seductive vocal was backed by hypnotic Afro-rhythms and dervish yelps".[40] Writing for MusicHound in 1999, Greg Kot opined that the same two songs were the "weakest cuts", adding: "Otherwise, the disc is a tour de force of acoustic-tinged savagery and slumming sexuality, particularly the gleefully flippant 'Stray Cat Blues.'"[43] Larry Katz from the Boston Herald called Beggars Banquet "both a return to basics and leap forward".[39]

In his 1997 review for Rolling Stone, DeCurtis said the album was "filled with distinctive and original touches", and remarked on its legacy: "For the album, the Stones had gone to great lengths to toughen their sound and banish the haze of psychedelia, and in doing so, they launched a five-year period in which they would produce their very greatest records."[6] Author Martin C. Strong similarly considers Beggars Banquet to be the first album in the band's "staggering burst of creativity" over 1968–72 that ultimately comprised four of the best rock albums of all time.[42] Writing in 2007, Daryl Easlea of BBC Music said that, although in places it fails to maintain the quality of its opening song, Beggars Banquet represented the Rolling Stones at their sharpest.[47]

Beggars Banquet has appeared on professional listings of the greatest albums. It was included in the "Basic Record Library" of 1950s and 1960s recordings published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981).[48] In 2000, it was voted number 282 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums.[49] In 2003, it was ranked at number 57 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[50] ranked at number 58 in a 2012 revised list,[51] and ranked at number 185 in a 2020 revised list.[52] Also in 2003, the TV network VH1 named Beggars Banquet the 67th greatest album of all time. The album is also featured in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[53] In 1999, the album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[54]

Reissues

[edit]In August 2002, ABKCO Records reissued Beggars Banquet as a newly remastered LP and SACD/CD hybrid disk.[55] This release corrected a flaw in the original album by restoring each song to its proper, slightly faster speed. Due to an error in the mastering, Beggars Banquet was heard for over thirty years at a slower speed than it was recorded. This had the effect of altering not only the tempo of each song, but the song's key as well. These differences were subtle but important, and the remastered version is about 30 seconds shorter than the original release.

Also in 2002 the Russian label CD-Maximum unofficially released the limited edition Beggars Banquet + 7 Bonus, which was also bootlegged on a German counterfeit-DECCA label as Beggars Banquet (the Mono Beggars).

It was released once again in 2010 by Universal Music Enterprises in a Japanese-only SHM-SACDversion and on 24 November 2010 ABKCO Records released a SHM-CD version.

On 28 May 2013 ABKCO Records reissued the LP on vinyl.

In 2018, the album was reissued for its 50th anniversary.[56]

Record Store Day Edition appeared on the British market on Saturday, 22 April 2023.[57]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, except "Prodigal Son" by Robert Wilkins.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sympathy for the Devil" | 6:18 |

| 2. | "No Expectations" | 3:56 |

| 3. | "Dear Doctor" | 3:28 |

| 4. | "Parachute Woman" | 2:20 |

| 5. | "Jigsaw Puzzle" | 6:06 |

| Total length: | 22:08 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Street Fighting Man" | 3:16 |

| 2. | "Prodigal Son" | 2:51 |

| 3. | "Stray Cat Blues" | 4:38 |

| 4. | "Factory Girl" | 2:09 |

| 5. | "Salt of the Earth" | 4:48 |

| Total length: | 17:42 | |

Personnel

[edit]The Rolling Stones

- Mick Jagger – lead vocals (all tracks), hand drum (1), backing vocals (3, 6), harmonica (4), maracas (6, 8)

- Keith Richards – electric guitars (1, 4, 8), acoustic guitars (2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10), electric slide guitar (5, 10), bass guitar (1, 6, 8), backing vocals (1, 3, 10), opening lead vocals (10)

- Brian Jones – acoustic slide guitar (2), acoustic guitar (1, 4), harmonica (3, 4, 7), Mellotron (5, 8), sitar (6), tambura (6), backing vocals (1)

- Bill Wyman – bass guitar (2, 4, 5, 10), double bass (3), backing vocals (1), shekere (1)

- Charlie Watts – drums (1, 3–8, 10), claves (2), tambourine (3), tabla (9), backing vocals (1)

Additional personnel

- Nicky Hopkins – piano (1–3, 5, 6, 8, 10), Mellotron, Farfisa organ (2)

- Rocky Dzidzornu – congas (1, 8, 9), cowbell (1)

- Ric Grech – fiddle (9)

- Dave Mason – shehnai (6)

- Michael Cooper, Marianne Faithfull, Anita Pallenberg – backing vocals (1)

- Watts Street Gospel Choir – backing vocals (10)

- Barry Feinstein – photography and art design

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1968–1969) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[62] | 3 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[63] | 3 |

| Finland (The Official Finnish Charts)[64] | 4 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[65] | 8 |

| Japanese Albums (Oricon)[66] | 124 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[67] | 2 |

| Sweden (Kvällstoppen)[68] | 16 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[69] | 3 |

| US Billboard 200[70] | 5 |

| Chart (2007) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[71] | 43 |

| Chart (2012) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| French Albums (SNEP)[72] | 197 |

| Chart (2018) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[73] | 44 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[74] | 156 |

| Swiss Albums (Schweizer Hitparade)[75] | 67 |

| Chart (2024) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Croatian International Albums (HDU)[76] | 8 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[77] | Gold | 35,000‡ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[78] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[79] release of 2006 |

Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[80] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Phill (July 2000). "Phill Brown, Recording the Rolling Stones' Classic, Beggar's Banquet". tapeop.com. TapeOp. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b Lester, Paul (10 July 2007). "These albums need to go to rehab". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Dimery 2011, p. 130.

- ^ Luhrssen & Larson 2017, p. 305.

- ^ "Rolling Stones singles".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i DeCurtis, Anthony (17 June 1997). "Review: Beggars Banquet". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on 31 January 2002. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Karnbach & Bernson 1997, p. 234.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2016, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Elliot 2002, p. 131.

- ^ Clayson 2008, pp. 165, 186, 245, 246

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2016, pp. 256–259.

- ^ Clayson 2008, p. 192, 246.

- ^ Myers, Marc (11 December 2013). "Keith Richards: 'I Had a Sound in My Head That Was Bugging Me'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 147.

- ^ Egan 2013, p. 79.

- ^ Photography, Barry Feinstein. "Barry Feinstein Photography". Barry Feinstein Photography. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Gibbs, Christopher Henry. "Beggars Banquet" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Springer, Matt (6 December 2013). "Why the Rolling Stones Had to Change 'Beggars Banquet' Cover". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Hayward, Mark; Evans, Mike (7 September 2009). The Rolling Stones: On Camera, Off Guard 1963–69. Pavilion. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-1-86205-868-2. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Our Work". Metro Imaging. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Clayson 2006, p. 65.

- ^ Clayson 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Clayson 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Norman 2001, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Bockris 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Davis 2001, p. 278–279, 536.

- ^ Norman 2001, p. 322.

- ^ a b Davis 2001, p. 275

- ^ a b Unterberger, Richie. "Beggars Banquet – The Rolling Stones". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Salewicz 2002, p. 154.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian (November 2002). "The Rolling Stones: Play With Fire". Uncut. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ a b Wyman 2002, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Uncredited writer (30 November 1968). "The Rolling Stones: Beggars Banquet (Decca)". Melody Maker. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 22 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Cannon, Geoffrey (10 December 1968). "The Rolling Stones: Beggars' Banquet (Decca SKL 4955)". The Guardian. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 17 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1969). "Robert Christgau's 1969 Jazz & Pop Ballot". Jazz & Pop. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (April 1969). "Kiddie music, singles and albums, middle-class soul, Biff Rose, miscellaneous, Stones and Beatles". Esquire. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2020 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ "Beggars Banquet [50th Anniversary Edition] by The Rolling Stones Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (16 February 2022). "Xgau Sez: February 2022". And It Don't Stop. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ a b Katz, Larry (16 August 2002). "Music; Stoned again; Band's early albums reissued in time for tour". Boston Herald. Scene section, p. S.21. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Larkin, Colin (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 7 (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- ^ Browne, David (20 September 2002). "Satisfaction?". Entertainment Weekly. No. 673. New York. p. 103. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ a b Strong, Martin C. (2004). The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). Canongate U.S. pp. 1292, 1294. ISBN 1-84195-615-5.

- ^ a b Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 950. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ "Review: Beggars Banquet". NME. London. 8 July 1995. p. 46.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones: Album Guide". rollingstone.com. Archived version retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ Fong-Torres, Ben (2 April 2008). "The Rolling Stones, Beggars Banquet". eMusic. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2013. Alt URL Archived 23 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (2007). "The Rolling Stones Beggars Banquet Review". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "A Basic Record Library: The Fifties and Sixties". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251. Archived from the original on 12 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 121. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Greatest Albums of All Time 2003 List". Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Beggars Banquet ranked 185th greatest album by Rolling Stone magazine". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Dimery 2011, p. 22.

- ^ "Grammy Hall of Fame Letter B". Grammy. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Christopher (24 August 2002). "Super audio CDs: The Rolling Stones Remastered". Billboard. p. 27.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones "Beggars Banquet (50th Anniversary Edition) – Out November 16". abkco.com. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "RSD 2023 Beggars Banquet Release". abkco.com. 23 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2016, pp. 246–273.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones | Official Website". Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Satanic Sessions – Midnight Beat – CD box sets

- ^ Babiuk & Prevost 2013, p. 290.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 5887". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. ISBN 978-951-1-21053-5.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005 (in Japanese). Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Hallberg, Eric (1993). Eric Hallberg presenterar Kvällstoppen i P 3: Sveriges radios topplista över veckans 20 mest sålda skivor 10. 7. 1962 - 19. 8. 1975. Drift Musik. p. 243. ISBN 9163021404.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". Hung Medien. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Lista prodaje 39. tjedan 2024" (in Croatian). HDU. 16 September 2024. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2023 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". Music Canada. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "British album certifications – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "American album certifications – The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Bockris, Victor (1992). Keith Richards: The Unauthorised Biography. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-174397-4.

- Clayson, Alan (2008). The Rolling Stones: Beggars Banquet. Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-8230-8397-8.

- Clayson, Alan (2006). The Rolling Stones Album File & Complete Discography. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 1844034941.

- Davis, Stephen (2001). Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. New York, NY: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0312-9.

- Dimery, Robert, ed. (2011). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-84403-699-8.

- Egan, Sean (2013). Keith Richards on Keith Richards interviews and encounters (1st ed.). Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-791-9.

- Elliot, Martin (2002). The Rolling Stones: Complete Recording Sessions 1962–2002. Cherry Red Books Ltd. ISBN 1-901447-04-9.

- Karnbach, James; Bernson, Carol (1997). The Complete Recording Guide to the Rolling Stones. Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-85410-533-7.

- Luhrssen, David; Larson, Michael (2017). Encyclopedia of Classic Rock. ABC-CLIO.

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (25 October 2016). The Rolling Stones All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press. ISBN 978-0-316-31773-3.

- Norman, Philip (2001). The Stones. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-07277-6.

- Salewicz, Chris (2002). Mick & Keith. London: Orion. ISBN 0-75281-858-9.Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-3074-5239-9.

- Wyman, Bill (2002). Rolling with the Stones. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7513-4646-2.

- Wyman, Bill (1997). Stone Alone. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306807831.

- Babiuk, Andy; Prevost, Greg (2013). Rolling Stones Gear: All the Stones' Instruments from Stage to Studio. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-092-2.

External links

[edit]- Beggars Banquet at Discogs (list of releases)

- The Rolling Stones albums

- 1968 albums

- Albums produced by Jimmy Miller

- Decca Records albums

- London Records albums

- Albums recorded at Olympic Sound Studios

- ABKCO Records albums

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Roots rock albums

- Albums recorded at Sunset Sound Recorders

- Country blues albums

- Country rock albums by English artists