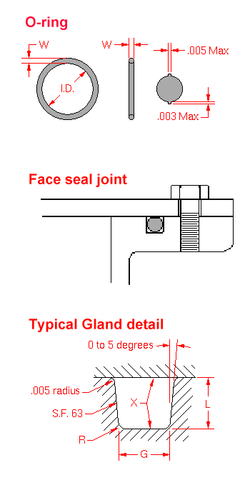

O-ring

An O-ring, also known as a packing or a toric joint, is a mechanical gasket in the shape of a torus; it is a loop of elastomer with a round cross-section, designed to be seated in a groove and compressed during assembly between two or more parts, forming a seal at the interface.

The O-ring may be used in static applications or in dynamic applications where there is relative motion between the parts and the O-ring. Dynamic examples include rotating pump shafts and hydraulic cylinder pistons. Static applications of O-rings may include fluid or gas sealing applications in which: (1) the O-ring is compressed resulting in zero clearance, (2) the O-ring material is vulcanized solid such that it is impermeable to the fluid or gas, and (3) the O-ring material is resistant to degradation by the fluid or gas.[1] The wide range of potential liquids and gases that need to be sealed has necessitated the development of a wide range of O-ring materials.[2]

O-rings are one of the most common seals used in machine design because they are inexpensive, easy to make, reliable, and have simple mounting requirements. They have been tested to seal up to 5,000 psi (34 MPa) of pressure.[3] The maximum recommended pressure of an O-ring seal depends on the seal hardness, material, cross-sectional diameter, and radial clearance.[4]

Manufacturing

[edit]O-rings can be produced by extrusion, injection molding, pressure molding, or transfer molding.[5]

History

[edit]The first patent for the O-ring is dated May 12, 1896, as a Swedish patent. J. O. Lundberg, the inventor of the O-ring, received the patent.[6] The US patent[7][8] for the O-ring was filed in 1937 by a then 72-year-old Danish-born machinist, Niels Christensen.[9] In his previously filed application in 1933, resulting in Patent 2115383,[10] he opens by saying, "This invention relates to new and useful improvements in hydraulic brakes and more particularly to an improved seal for the pistons of power conveying cylinders." He describes "a circular section ring ... made of solid rubber or rubber composition", and explains, "this sliding or partial rolling of the ring ... kneads or works the material of the ring to keep it alive and pliable without deleterious effects of scuffing which are caused by purely static sliding of rubber upon a surface. By this slight turning or kneading action, the life of the ring is prolonged." His application filed in 1937 says that it "is a continuation-in-part of my copending application Serial No. 704,463 for Hydraulic brakes, filed December 29, 1933, now U. S. Patent No. 2,115,383 granted April 26, 1938".

Soon after migrating to the United States in 1891, he patented an air brake system for streetcars (trams). Despite his legal efforts, the patents were passed from company to company until they ended up at Westinghouse.[9] During World War II, the US government commandeered the O-ring patent as a critical war-related item and gave the right to manufacture to other organizations. Christensen received a lump sum payment of US$75,000 for his efforts. Litigation resulted in a $100,000 payment to his heirs in 1971, 19 years after his death.[9]

Theory and design

[edit]

O-rings are available in various metric and inch standard sizes. Sizes are specified by the inside diameter and the cross section diameter (thickness). In the US the most common standard inch sizes are per SAE AS568C specification (e.g. AS568-214). ISO 3601-1:2012 contains the most commonly used standard sizes, both inch and metric, worldwide. The UK also has standards sizes known as BS sizes, typically ranging from BS001 to BS932. Several other size specifications also exist.

Typical applications

[edit]Successful O-ring joint design requires a rigid mechanical mounting that applies a predictable deformation to the O-ring. This introduces a calculated mechanical stress at the O-ring contacting surfaces. As long as the pressure of the fluid being contained does not exceed the contact stress of the O-ring, leaking cannot occur. The pressure of the contained fluid transfers through the essentially incompressible O-ring material, and the contact stress rises with increasing pressure. For this reason, an O-ring can easily seal high pressure as long as it does not fail mechanically. The most common failure is extrusion through the mating parts.

The seal is designed to have a point contact between the O-ring and sealing faces. This allows a high local stress, able to contain high pressure, without exceeding the yield stress of the O-ring body. The flexible nature of O-ring materials accommodates imperfections in the mounting parts. But it is still important to maintain good surface finish of those mating parts, especially at low temperatures where the seal rubber reaches its glass transition temperature and becomes increasingly inflexible and glassy. Surface finish is also especially important in dynamic applications. A surface finish that is too rough will abrade the surface of the O-ring, and a surface that is too smooth will not allow the seal to be adequately lubricated by a fluid film.

Vacuum applications

[edit]In vacuum applications, the permeability of the material renders the point contacts unusable. Instead, higher mounting forces are used and the ring fills the whole groove. Also, round back-up rings are used to save the ring from excessive deformation.[12][13][14]

Because the ring is subject to the ambient pressure and the partial pressure of gases only at the seal, their gradients will be steep near the seal and shallow in the bulk (opposite to the gradient of the contact stress[15] (See Vacuum flange#KF.2FQF.) High-vacuum systems below 10−9 Torr use copper or nickel O-rings. Also, vacuum systems that have to be immersed in liquid nitrogen use indium O-rings, because rubber becomes hard and brittle at low temperatures.

High temperature applications

[edit]In some high-temperature applications, O-rings may need to be mounted in a tangentially compressed state, to compensate for the Gow-Joule effect.

Sizes

[edit]O-rings come in a variety of sizes. Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) Aerospace Standard 568 (AS568)[16] specifies the inside diameters, cross-sections, tolerances, and size identification codes (dash numbers) for O-rings used in sealing applications and for straight thread tube fitting boss gaskets. British Standard (BS) which are imperial sizes or metric sizes. Typical dimensions of an O-ring are internal dimension (id), outer dimension (od), and thickness / cross section (cs)

Metric O-rings are usually defined by the internal dimension x the cross section. Typical part number for a metric O-ring - ID x CS [material & shore hardness] 2x1N70=defines this O-ring as 2mm id with 1mm cross section made from Nitrile rubber which is 70Sh. BS O-rings are defined by a standard reference.

The World's Largest O-ring was produced in a successful Guinness World Record attempt by Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Tewkesbury partnered with a group of 20 students from Tewkesbury School. The O-ring once finished and placed around the Medieval Tewkesbury Abbey had a 364 m (1,194 ft) circumference, an approximately 116 m (381 ft) inner diameter, and a cross section of 7.2 mm (0.28 in).[17]

Material

[edit]

O-ring selection is based on chemical compatibility, application temperature, sealing pressure, lubrication requirements, durometer, size, and cost.[18]

Synthetic rubbers - Thermosets:

- Butadiene rubber (BR)

- Butyl rubber (IIR)

- Chlorosulfonated polyethylene (CSM)

- Epichlorohydrin rubber (ECH, ECO)

- Ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM): good resistance to hot water and steam, detergents, caustic potash solutions, sodium hydroxide solutions, silicone oils and greases, many polar solvents, and many diluted acids and chemicals. Special formulations are excellent for use with glycol-based brake fluids. Unsuitable for use with mineral oil products: lubricants, oils, or fuels. Peroxide-cured compounds are suitable for higher temperatures.[19]

- Ethylene propylene rubber (EPR)

- Fluoroelastomer (FKM): noted for their very high resistance to heat and a wide variety of chemicals. Other key benefits include excellent resistance to aging and ozone, very low gas permeability, and the fact that the materials are self-extinguishing. Standard FKM materials have excellent resistance to mineral oils and greases, aliphatic, aromatic, and chlorinated hydrocarbons, fuels, non-flammable hydraulic fluids (HFD), and many organic solvents and chemicals. Generally not resistant to hot water, steam, polar solvents, glycol-based brake fluids, and low molecular weight organic acids. In addition to the standard FKM materials, a number of specialty materials with different monomer compositions and fluorine content (65% to 71%) are available that offer improved chemical or temperature resistance and/or better low temperature performance.[19]

- Nitrile rubber (NBR, HNBR, HSN, Buna-N): a common material for o-rings because of its good mechanical properties, its resistance to lubricants and greases, and its relatively low cost. The physical and chemical resistance properties of NBR materials are determined by the acrylonitrile (ACN) content of the base polymer: low content ensures good flexibility at low temperatures, but offers limited resistance to oils and fuels. As the ACN content increases, the low temperature flexibility reduces and the resistance to oils and fuels improves. Physical and chemical resistance properties of NBR materials are also affected by the cure system of the polymer. Peroxide-cured materials have improved physical properties, chemical resistance, and thermal properties, as compared to sulfur-donor-cured materials. Standard grades of NBR are typically resistant to mineral oil-based lubricants and greases, many grades of hydraulic fluids, aliphatic hydrocarbons, silicone oils and greases, and water to about 176 °F (80 °C). NBR is generally not resistant to aromatic and chlorinated hydrocarbons, fuels with a high aromatic content, polar solvents, glycol-based brake fluids, and non-flammable hydraulic fluids (HFD). NBR also has low resistance to ozone, weathering, and aging. HNBR has considerable improvement of the resistance to heat, ozone, and aging, and gives it good mechanical properties.[19]

- Perfluoroelastomer (FFKM)

- Polyacrylate rubber (ACM)

- Polychloroprene (neoprene) (CR)

- Polyisoprene (IR)

- Polysulfide rubber (PSR)

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)

- Sanifluor (FEPM)

- Silicone rubber (SiR): noted for their ability to be used over a wide temperature range and for excellent resistance to ozone, weathering, and aging. Compared with most other sealing elastomers, the physical properties of silicones are poor. Generally, silicone materials are physiologically harmless so they are commonly used by the food and drug industries. Standard silicones are resistant to water up to 212 °F (100 °C), aliphatic engine and transmission oils, and animal and plant oils and fats. Silicones are generally not resistant to fuels, aromatic mineral oils, steam (short term to 248 °F (120 °C) is possible), silicone oils and greases, acids, or alkalis. Fluorosilicone elastomers are far more resistant to oils and fuels. The temperature range of applications is somewhat more restricted.[19]

- Styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR)

- Thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) styrenics

- Thermoplastic polyolefin (TPO) LDPE, HDPE, LLDPE, ULDPE

- Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) polyether, polyester: Polyurethanes differ from classic elastomers in that they have much better mechanical properties. In particular they have a high resistance to abrasion, wear, and extrusion, a high tensile strength, and excellent tear resistance. Polyurethanes are generally resistant to aging and ozone, mineral oils and greases, silicone oils and greases, nonflammable hydraulic fluids HFA & HFB, water up to 122 °F (50 °C), and aliphatic hydrocarbons.[19]

- Thermoplastic etheresterelastomers (TEEEs) copolyesters

- Thermoplastic polyamide (PEBA) Polyamides

- Melt Processible Rubber (MPR)

- Thermoplastic Vulcanizate (TPV)

- Air, 200 to 300 °F (93 to 149 °C) – Silicone

- Beer - EPDM

- Chlorine Water – Viton (FKM)

- Gasoline – Buna-N or Viton (FKM)

- Hydraulic Oil (Petroleum Base, Industrial) – Buna-N

- Hydraulic Oils (Synthetic Base) – Viton

- Water – EPDM

- Motor Oils – Buna-N[20]

Other seals

[edit]

Although the O-ring was originally so named because of its circular cross section, there are now variations in cross-section design. The shape can have different profiles, such as an x-shaped profile, commonly called the X-ring, Q-ring, or by the trademarked name Quad Ring. When squeezed upon installation, they seal with 4 contact surfaces—2 small contact surfaces on the top and bottom.[21] This contrasts with the standard O-ring's comparatively larger single contact surfaces top and bottom. X-rings are most commonly used in reciprocating applications, where they provide reduced running and breakout friction and reduced risk of spiraling when compared to O-rings.

There are also rings with a square profile, commonly called square-cuts, lathe cuts, tabular cut, or square rings. When O-rings were selling at a premium because of the novelty, lack of efficient manufacturing processes, and high labor content, square rings were introduced as an economical substitution for O-rings. The square ring is typically manufactured by molding an elastomer sleeve which is then lathe-cut. This style of seal is sometimes less expensive to manufacture with certain materials and molding technologies (compression molding, transfer molding, injection molding), especially in low volumes. The physical sealing performance of square rings in static applications is superior to that of O-rings, however in dynamic applications it is inferior to that of O-rings. Square rings are usually used only in dynamic applications as energizers in cap seal assemblies. Square rings can also be more difficult to install than O-rings.

Similar devices with a non-round cross-sections are called seals, packings, or gaskets. See also Washer (hardware).[22]

Automotive cylinder heads are typically sealed by flat gaskets faced with copper.

Knife edges pressed into copper gaskets are used for high vacuum.

Elastomers or soft metals that solidify in place are used as seals.

Failure modes

[edit]O-ring materials may be subjected to high or low temperatures, chemical attack, vibration, abrasion, and movement. Elastomers are selected according to the situation.

There are O-ring materials which can tolerate temperatures as low as −330 °F (−200 °C) or as high as 480 °F (250 °C). At the low end, nearly all engineering materials become rigid and fail to seal; at the high end, the materials often burn or decompose. Chemical attack can degrade the material, start brittle cracks or cause it to swell. For example, NBR seals can crack when exposed to ozone gas at very low concentrations, unless protected. Swelling by contact with a low viscosity fluid causes an increase in dimensions, and also lowers the tensile strength of the rubber. Other failures can be caused by using the wrong size of ring for a specific recess, which may cause extrusion of the rubber.

Elastomers are sensitive to ionizing radiation. In typical applications, O-rings are well-protected from less-penetrating radiation such as ultraviolet and soft X-rays, but more-penetrating radiation such as neutrons may cause rapid deterioration. In such environments, soft metal seals are used.

There are a few common reasons for O-ring failure:

- Installation damage – This is caused by improper installation of the O-ring.

- Spiral failure – Found on long-stroke piston seals and – to a lesser degree – on rod seals. The seal gets "hung up" at one point on its diameter (against the cylinder wall) and slides and rolls at the same time. This twists the O-ring as the sealed device is cycled and finally causes a series of deep spiral cuts (typically at a 45-degree angle) on the surface of the seal.

- Explosive decompression – An O-ring embolism, also called gas expansion rupture, occurs when high pressure gas becomes trapped inside the elastomeric seal element. This expansion causes blisters and ruptures on the surface of the seal.

Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

[edit]The failure of an O-ring seal was determined to be the cause of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster on January 28, 1986. A crucial factor was cold weather prior to the launch. This was famously demonstrated on television by Caltech physics professor Richard Feynman, when he placed a small O-ring into ice-cold water, and subsequently showed its loss of flexibility before an investigative committee.

The material of the failed O-ring was FKM, which was specified by the shuttle motor contractor, Morton-Thiokol. When an O-ring is cooled below its glass transition temperature Tg, it loses its elasticity and becomes brittle. More importantly, when an O-ring is cooled near (but not beyond) its Tg, the cold O-ring, once compressed, will take longer than normal to return to its original shape. O-rings (and all other seals) work by producing positive pressure against a surface, thereby preventing leaks. On the night before the launch, exceedingly low air temperatures were recorded. Due to this, NASA technicians performed an inspection; the ambient temperature was within launch parameters, and the launch sequence was allowed to proceed. However, the temperature of the rubber O-rings remained significantly lower than that of the surrounding air. During his investigation of the launch footage, Feynman observed a small out-gassing event from the Solid Rocket Booster at the joint between two segments in the moments immediately preceding the disaster. This was blamed on a failed O-ring seal. The escaping high-temperature gas impinged upon the external tank, and the entire vehicle was destroyed as a result.

Since the accident, rubber production companies have enacted changes. Many O-rings now come with batch and cure-date coding, as is done in medicine production, to precisely track and control distribution. For aerospace and military applications, O-rings are usually individually packaged and labeled with the material, cure date, and batch information. O-rings can, if needed, be recalled off the shelf.[23] Furthermore, O-rings and other seals are routinely batch-tested for quality control by the manufacturers, and often undergo quality assurance testing several more times by the distributor and ultimate end-users.

As for the boosters themselves, NASA and Morton-Thiokol redesigned them with a new joint design, which now incorporated three O-rings instead of two, with the joints themselves having onboard heaters that can be turned on when temperatures drop below 50 °F (10 °C). No O-ring issues have occurred since Challenger, and they did not play a role in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster of 2003.

Standards

[edit]ISO 3601 Fluid power systems — O-rings

[edit]- ISO 3601-1:2012 Inside diameters, cross-sections, tolerances and designation codes

- ISO 3601-2:2016 Housing dimensions for general applications

- ISO 3601-4:2008 Anti-extrusion rings (back-up rings)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Whitlock, Jerry (2004). "The Seal Man's O-Ring Handbook" (PDF). EPM, Inc. - The Seal Man. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-10. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ "GFS O-Rings". Gallagher Seals. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Pearl, D.R. (January 1947). O-Ring Seals in the Design of Hydraulic Mechanisms. S.A.E. Annual Meeting. Hamilton Standard Prop. Div. of United Aircraft Corp.

- ^ "Frequently Asked O-ring Technical Questions". Parker O-Ring & Engineered Seals Division. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ "Factory Tour".

- ^ "O-Ring - Who Invented the O-Ring?". Inventors.about.com. 2010-06-15. Archived from the original on 2009-03-15. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ US patent 2180795, Niels A. Christensen, issued 1939-11-21

- ^ 2180795, Christensen, Niels A., "Packing", issued 1939-11-21, applied 1937-10-02

- ^ a b c "No. 555: O-Ring". Uh.edu. 2004-08-01. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ 2115383, Christensen, Niels A., "Hydraulic brake", issued 1938-04-26, applied 1933-12-29

- ^ U.S. patent 5,516,122

- ^ "Nor-Cal Products, Inc. - NW Stainless Steel Centering Rings with O-ring". Archived from the original on 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ "MDC Vacuum Products-Vacuum Components, Chambers, Valves, Flanges & Fittings". Mdc-vacuum.com. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ "O-ring". Glossary.oilfield.slb.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ "DHCAE Tools GMBH: OpenFOAM-solution".

- ^ "AS568: Aerospace Size Standard for O-Rings - SAE International". sae.org. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Trelleborg Sets Guinness World Record for the Largest O-Ring Ever Produced".

- ^ "O-ring Design, O-ring Design Guide, O-ring Seal Design -Mykin Inc". Mykin.com. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ a b c d e "Type details". O-ring elastomer. Dichtomatik Americas. 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Chemical Compatibility". The O-Ring Store LLC.

- ^ "X-ring simulation".

- ^ "John Crane seals measure up to API standards: News from John Crane EAA". Processingtalk.com. 2005-12-09. Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ "What is O-Ring Shelf Life?". Oringsusa.com. Retrieved 2011-03-25.